A Musical Literary Analysis on Nakuru Aitsuki's "FAKE IDOL"

Performance is Erasure

Content note: This analysis discusses themes of self-harm, suicidal ideation, substance abuse, and psychological exploitation within the entertainment industry. Reader discretion is advised.

Introduction

What follows is my interpretation of "FAKE IDOL", the interpretation that emerged from sitting with this song, its lyrics, and its MV over and over again. Symbolism rarely has only one meaning, and I don't believe this song can be reduced to a single, definitive message. This is simply the lens through which it resonated most strongly with me. Likewise, while this analysis engages critically with idol culture and the entertainment industry, it is not a claim about every idol or every entertainer. Many artists find joy, agency, and fulfillment in their work. This song, however, tells a much darker story, and it’s that story, as I understand it, that I want to explore here.

For readers unfamiliar with Japanese idol culture: "idols" are entertainers whose work is built not only on music or performance, but on the cultivation of approachability, emotional intimacy, and constant availability. Fans are encouraged to feel personally connected to idols through social media, events, and direct-address marketing, while idols are often expected to maintain carefully controlled public personas—cheerful, pure, and endlessly accommodating. Unlike Western pop stardom, where distance and mystique are often part of the appeal, idol culture frequently rewards accessibility and emotional labor, blurring the line between performer and product.

Before I start, I recommend that you watch the MV (music video) in full first (it's only 3 minutes) and read through a translation of the lyrics (big thanks to tetrax4berium) in order to have a surface level understanding of the song first, before reading this analysis.

Opening

The MV doesn't ease us in gently. As the first major note plays, we see the idol collapsed on the ground, surrounded by the objects that define her entire existence:

- A phone lying beside her right hand, which is the source of constant notifications, the demand for perpetual digital presence, and the device that ensures she's never truly alone or off-duty

- Pills scattered to her left, which symbolize the management of an unsustainable lifestyle through drug use

- Lightsticks, which for the idol are symbols of the fan devotion that both sustains and suffocates her, glowing with the parasocial love that demands everything and gives nothing back

- An envelope, which may symbolize fan mail requiring responses, or perhaps contract documents that legally bind her to this existence. Either way, it's communication that flows one direction: demands placed upon her

- A red jar or container, which also happens to be the only warm color in this cold blue scene. Given the context of medication and later references to alcohol, this might be energy drinks, supplements, more medication, or alcohol.

The geometric composition itself of this scene is significant as well. Look at the positioning of these objects around the idol, she's surrounded by them. They form a perimeter around her collapsed body, enclosing her completely. There's not much empty space in this frame. Every direction she could reach is another tool of her exploitation or another demand on her existence.

However, what's most devastating about this opening shot is what it doesn't show us. We're not introduced to a person with a name, a history, or a personality. We're introduced to the sum of her tools and obligations. The objects define her more than any personal characteristic does. It's like looking at a crime scene, and we're about to spend the next three minutes learning exactly how each of these objects contributed to the death of whoever she used to be.

Pre-Chorus

The very first lines establish the core conflict of the song:

四六時中響く通知音 (The notifications keep ringing throughout the day.)

ハートマークの裏の素顔は (The person behind the persona and the "likes")

観測されなければ存在しない (Wouldn't exist if they're not perceived.)

This establishes the fundamental horror of her existence, a reference to quantum mechanics' observer effect, but applied to human existence. She has so completely internalized the idol system that she literally ceases to exist when not being watched. The "idol" self is completely erasing the "original" self.

The next line drives this home with devastating clarity:

こんな私は私で在り得ない (It's unbelievable that I'd live like this.)

The verb "在り得ない" (arienai) carries both impossibility and moral revulsion. It showcases that this state of being is fundamentally wrong, yet it persists. She recognizes the ontological violence being done to her, but she's trapped within it, unable to escape.

あーね、そうねお互い様 (Ahh~ Hey, it's the same for you, right?)

行くも戻すもどうせ地獄なの (It's the same hell, regardless of whether I leave or return.)

The phrase "お互い様" (otagai-sama, "it's the same for both of us") is interesting, and I think intentionally vague. It could mean the fans are equally trapped in this parasocial relationship, unable to exist without their idol fixations; or it could mean that anyone in this industry faces the same impossible choice, either

- destroy yourself by staying

- or destroy yourself by leaving

Either way, there's no escape.

The Medicated Spiral

頼ってしまう眠剤 overdose (I end up relying on sleeping pills till I overdose.)

歪む 歪む わたしはだあれ? (Everything's warped and distorted. Who exactly am I?)

These lines immediately reminded me of Judy Garland, who is one of the most popular examples of how the entertainment industry destroys its performers. While working for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios, Judy Garland was prescribed multiple types of drugs, which were allegedly given at the direct order of Louis B. Mayer, who was the co-founder of MGM[1]

"They'd give us pep pills," she recalled, "then they'd take us to the studio hospital and knock us cold with sleeping pills... after four hours they'd wake us up and give us pep pills again...that's the way we worked, and that's the way we got thin. That's the way we got mixed up. And that's the way we lost contact." — Judy Garland

The parallel between this and the idol in FAKE IDOL is strikingly similar. Both the 1940s Hollywood studio system and modern idol culture use drugs to make the human body conform to an inhuman production schedule. For the idol, the pills in the opening shot were ultimately less a choice than a job requirement.

Chorus

ちゅっちゅっちゅるっちゅ~ (Chu Chu Churu Chu~)

君のせいだよ (It's all your fault)

The "ちゅっちゅっちゅるっちゅ" kissing sounds are aggressively, almost grotesquely cutesy. This symbolizes the kind of affection expected of Japanese idols; infantilizing, innocent performances designed to evoke protective and possessive feelings in their fans.

But embedded within this manufactured cuteness is the accusation "君のせいだよ" (It's your fault).

Whose fault? The fans who demand this performance? The industry that profits from it? The toxic society that creates these expectations? Herself, for accepting this role? The ambiguity is deliberate. Everyone is complicit, no one is responsible.

The chorus continues:

いつだって絶好調! はいどーぞ! (I'm always in my best condition, here you go!)

って Love you! だよ forever ("I Love you forever!")

She says "I'm always in my best condition", even though we've just been told of the sleeping pill overdoses and identity dissolution. The bright and cutesy delivery can't hide what he already know. This is what sociologist Arlie Hochschild calls "emotional labor"[2], selling not just a performance but authentic-seeming emotion, which paradoxically requires destroying your actual emotions to maintain the performance.

私が私でいる限りは キラキラを届けるよ (I'll deliver this sparkling excitement for as long as I am me.)

私が私でいる限りは ずっと笑っているから (I'll always be smiling for as long as I am me.)

But which me? tetrax4berium's English translation wisely emphasizes the word me in this context throughout the translation to indicate that this refers to the idol's persona, not the authentic person. She'll keep delivering sparkles and smiles "for as long as I am me", but she's only herself (the idol) by not being her true self (the person).

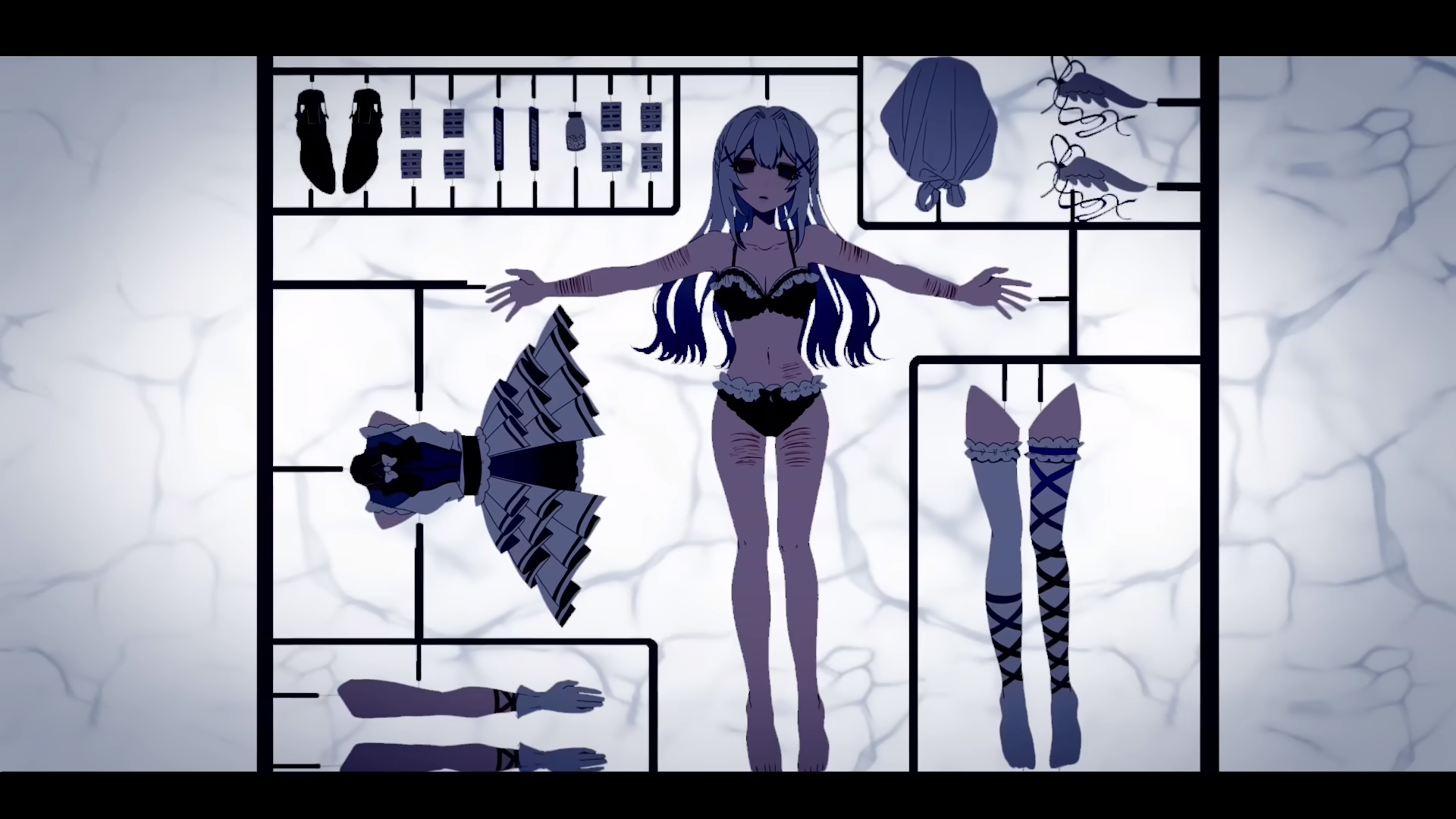

The Doll Sequence

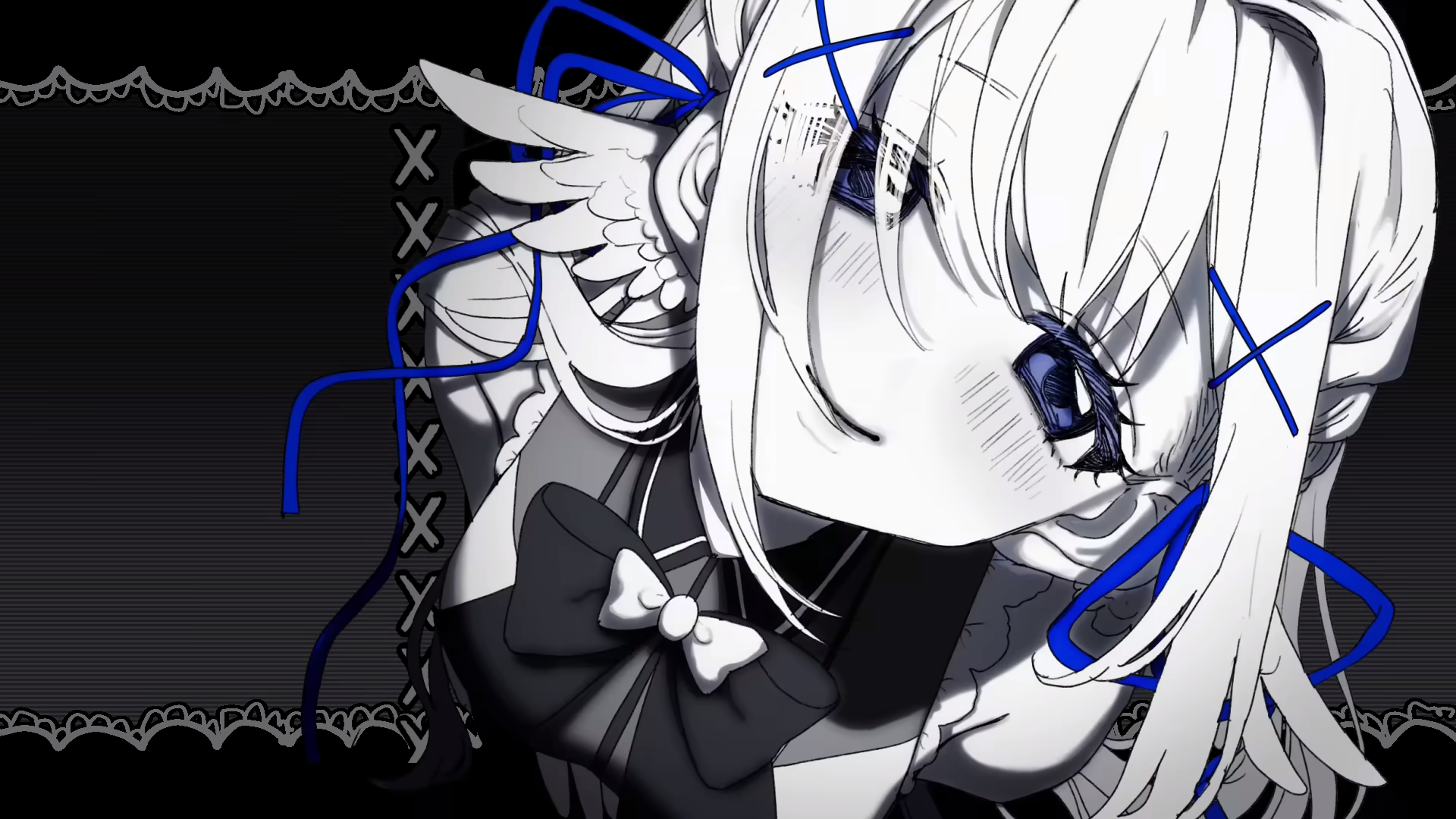

After the first chorus, the MV gives us its most powerful and disturbing metaphor, the idol as a doll with removable body parts. Her body bears multiple visible self-harm scars. Then hands, not her own, maybe her management or industry forces, begin replacing the scarred parts with "clean" ones, dressing the doll in a complete idol outfit.

As the new head is about to be placed, we see her face. She looks terrified. She's on the verge of tears, clearly unwilling, but the replacement happens anyway.

As the scarred parts are replaced, the MV repeatedly cuts to a jigsaw puzzle, slowly being completed. As the final part, the head, is placed, the puzzle is completed, showing a portrait of the idol smiling.

The sequence embodies the song's horror. The idol is assembled, not autonomous. Her body isn't hers, it's a collection of interchangeable parts to be optimized for profitability. The self-harm scars, which to her are the evidence of her humanity, her suffering, her reality, must be covered up because they disrupt the product.

Not only that, the jigsaw imagery shows that the "whole" person is only achieved by assembling the public idol persona. The real, fractured person, remains unsolved, because solving it would require completely destroying the idol image. Her completeness requires her erasure.

The Labor of Beauty

みてくれと引き換えに (In exchange for this spotlight)

梳けば溶けていく髪 煩わしくって嫌ね (I have to maintain and comb this melting hair.

I hate it for how annoying it is.)

Even beauty, which is the supposed currency of her profession, becomes a burden to her. The "melting hair" (tetrax4berium's English translation keeps this literal, probably referring to the colored hair she has in the MV) isn't a source of enjoyment, it's a source of labor. Every aspect of her appearance is work, and that work is never finished.

騙してんじゃない 足りないんだ愛 (I'm not deceiving anyone… All this love ain't enough…)

涙落ちる音がした (The sound of dripping tears can be heard.)

She's not a con artist, and she's genuinely trying to provide what's demanded of her, but the fans' love, despite being her entire livelihood, can never fill the void where her authentic self used to be. The love is for an image, not a person, and she knows it.

Self-Harm as Proof of Existence

Subsequently, we reach some of the most devastating lines in the entire song

“自分”なんてない どれ?分かんない (I don't feel like "Myself". Which self? I don't know.)

理想も見失ったわ (I've even lost sight of my ideals.)

血を流す度 確かな痛み (Each time I bleed, the undeniable pain)

お人形じゃない証よ (Is proof I'm not a doll.)

ちょっと救われた気になって (With that, I feel like I've found a little salvation.)

When your entire life is based on performance, when your very existence depends on being observed and consumed, physical pain becomes the only authentic experience. For the idol, self-harm has become her confirmation of existence. Physical pain is something that can't be faked, can't be performed, and can't be commodified by her audience. It's hers alone, and therefore it's the only thing that's real.

The Japanese is even more specific than what tetrax4berium's English translation originally conveys. "血を流す度" means "each time I bleed", suggesting this isn't accidental injury but repeated, ritualized self-verification. And she finds "救われた" (salvation) in it. Not healing, but salvation. In a life contingent on everything being a performance, this ritualized suffering becomes something sacred, as it is the only proof that one is still human.

The phrase "お人形じゃない証よ" (proof I'm not a doll) is particularly loaded. "Doll" here means someone with no autonomy, no thoughts, no feelings, existing only to be observed. The MV has just shown us the literal doll with replaceable parts. She needs to prove to herself that she's not a doll, and the best proof available to her is pain.

In my mind, this once again connects directly back to Judy Garland, who attempted suicide multiple times throughout her career and eventually died of a barbiturate overdose at age 47. Near the end of her life, performing while visibly unwell, she was still beloved by audiences who considered her concerts transformative experiences. They loved watching her survive her suffering, which meant her suffering could never end, because it had become part of the performance.

The Only Refuge is Hell

"可愛いってその言葉 ("Of course, there are times I think this isn't all that bad,)

満更でもない時もそりゃあるよ (Like when I receive compliments calling me cute.)

でもあなたは本当を知らない (But you don't really know the real me—)

決してそんな、そんな綺麗なものなんかじゃない (There's no way that I could be beautiful like that.)

This is a moment of painful honesty. Yes, sometimes the validation feels good. Sometimes being called cute doesn't feel entirely hollow. But those moments can't sustain her because the person being praised isn't her. But the "real" person, the messy, suffering, human person, would disrupt the fantasy. And the fantasy is what pays the bills.

刃物を持ってトイレに走るようなこの衝動に (This urge—like rushing to the bathroom with a blade in hand)

夜な夜なアルコールで蓋をする (Night after night I seal it away with alcohol)

This is, in my opinion, one of the darkest parts of the song. It sounds like she's considered suicide multiple times (hence the "night after night"), and she quells that desire to end it all by drinking the pain away.

逃げ出そうにも私の居場所はここなんだと (Even if I want to escape, this is the only refuge for me.)

誰かが今日も囁くの (I can hear somebody whispering again today)

She can see that this industry is destroying her from the inside out. She wants to escape. But this is her only source of income, identity, and belonging.

Who is the "somebody whispering"? In my opinion, it's her own voice, in a state of drunken clarity, telling her truths she can't face sober.

この感情も何もかも この世界の何もかも (Of everything in this world, and of all these emotions)

あなたのことも、この私のことも知らないで (Where I know nothing about you, and you understand nothing of me)

ただ普通に生きることを (If we're just living our normal lives)

幸せって言うのかな" (Would I say that I'm happy then?")

The parasocial relationship is exposed as mutual ignorance. The fans know nothing real about her. She knows nothing real about them. The "love" between them is just a transaction with no actual intimacy. And somewhere, underneath all the performance, is a person who just wants to live a normal life, something that has become permanently inaccessible.

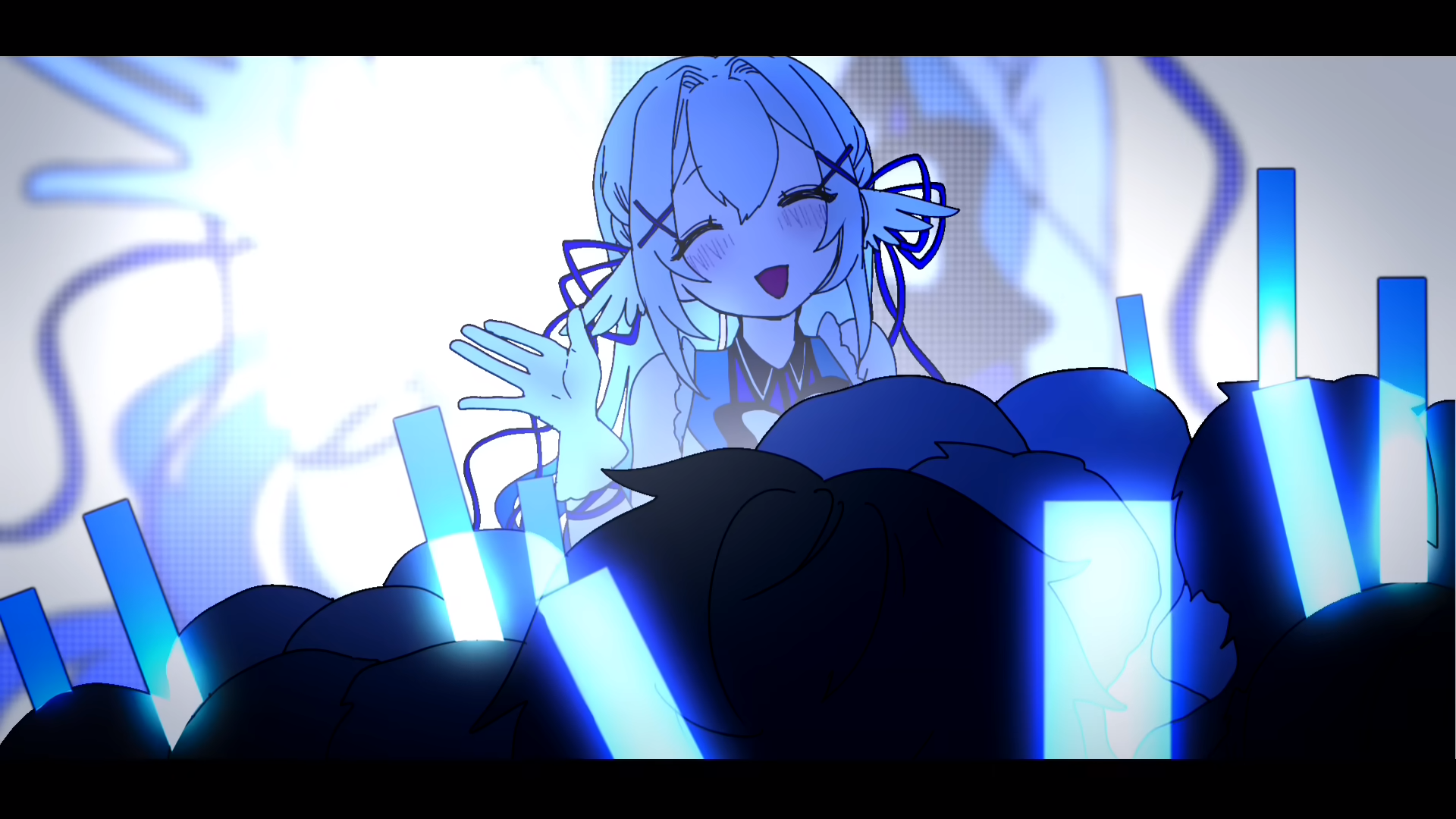

The Third Chorus

さよならはまだ… (It's not yet time to say goodbye…)

This line, synchronized with the MV transition of the idol popping out of a funeral image, is fascinating. She decides to return from her "death" (the collapse, the breakdown, the funeral imagery) and take up the idol persona again. She's not ready to say goodbye, but not because she's healed, because she has no other choice.

By the final chorus, the performance is barely holding together. Her voice shakes audibly on "ちゅっちゅっちゅるっちゅ." The cutesy affectation sounds desperate now, like someone clinging to a script because it's the only thing keeping them upright.

Near the end of the final repetition of the chorus:

私が私でいる限りは キラキラを届けるよ (I'll deliver this sparkling excitement for as long as I am me.)

私が私でいる限りは ずっと笑っているから (I'll always be smiling for as long as I am me.)

She says once again, "I'll always be smiling." Not "I'll always be happy", but smiling. The performance of happiness. The promise is both reassurance and threat: This will never end. As long as the idol-self exists, the performance continues.

The Final Line: Love the Fake ("Real") Me

明日も明後日もその先も (For tomorrow, the day after tomorrow, and for all the days ahead)

"本物"の私を愛してね (Please continue to love this Fake ["Real"] version of Me.)

Even after revealing the complete destruction of her authentic self, after showing us the self-harm and the alcohol, after all of that, she asks us to love the "本物" (honmono), the "real" her.

But the "real" is the fake. The authentic self no longer exists to be loved. What remains is the performance of the "perfect" idol. The audience gets what it always wanted. The perfect idol, with no inconvenient humanity underneath.

Conclusion: The Question the Song Leaves With Us

"FAKE IDOL" doesn't offer solutions. It doesn't end with the protagonist escaping or healing or finding her authentic self. It ends with her putting the mask back on and promising to keep performing forever.

The question it leaves us with is this: Knowing all of this, will we keep watching? Will we keep loving the fake ("real") her?

And if we do keep consuming idol content, keep streaming the songs, keep buying the merch, keep participating in the parasocial relationships, what does that make us?

This doesn't apply just to her, not even to Japan. The problems this song talks about are universal across the entertainment industry, especially here in America in Hollywood.

Knowing what the entertainment industry worldwide has put its talents through for over a century at this point, will we keep supporting this system?

I don't have a comfortable answer. I've listened to this song dozens of times while writing this analysis. I've contributed to its view count. I've shared it with others. Knowing the subject matter of the song, I participate anyway because the song is too good, too catchy, and too affecting to stop engaging with.

Maybe at the end of the day, that's the real horror. Not that the system exists, but that we can see it clearly and still won't stop, because what it produces is too good to not engage with. The idol keeps performing because she has no choice. What's our excuse?